Review: Errementari (2017)

It’s a bold move to have a straight-up devil in your horror film. It runs the risk of being too on the nose, I’d think. I’m not talking possession. Not talking demon. I’m not even saying THE DEVIL. Just a devil, no “the.” A pointy tale, pitch-fork using, red skinned, horned, devil. Bold, but Errementari: The Blacksmith and the Devil is strangely more unique and interesting in its use of cliche imagery than if it went for something less obvious.

Do we need another monster or demon with a big mouth and tiny eyes like something out of Gears of War, which seems to be the character design du jour?

Instead, this Basque folklore inspired horror film is a more fresh and original plot, setting, and feel than most of its contemporaries due to its cultural touchstones and traditional imagery.

The appeal of Errementari(my dear Watson) is primarily centered around three things:

- Its Basque country setting, taking place in the mid 19th century towards the end of the Carlist war.

- Its Del Toro-esque child’s dark fairy tale perspective.

- Its Basque folklore roots.

Regarding the first point:

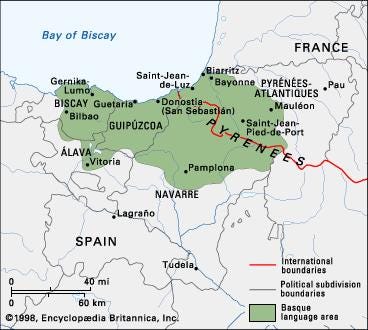

Errementari takes place in Basque country, which for those of you who, like me, didn’t really know where that was, is situated mostly in Spain at the border of Spain and France. Think Pamplona type places.

Beautiful, but historically treacherous, war-torn country.

The film is, similarly to Benecio Del Toro’s flawless Pan’s Labyrinth, situated during (but not focused directly upon) the ending of a devastating civil war. The 20th century Spanish Civil War in the case of Pan’s Labyrinth, the First Carlist War, for Errementari.

The First Carlist War took place between 1833 to 1840, fought between warring factions of the royal family regarding succession and the future of Spanish governance. Think Game of Thrones, Stannis Baratheon vs Cersei, sort of.. The Carlists’ wanted to return to a more traditional absolute monarchy. Surrounding countries interfered to lend a hand to the opposing pro-regency forces.

The war effort took a particularly heavy toll on Basque Country economics, its people weary of Carlos’s disregard for the their wish of autonomy.

The war ended in ’39 with the the Basques managing to keep a reduced version of their previous home rule in exchange for their absorption into the country of Spain. But by 1841, Basque country was occupied again by an uprising, resulting in an eventual repeal of Basque independence. The region was gripped by a wave of famine, and many fled overseas places like America.

All of that feeds into the smoky, moody, tense setting we see in Errementari, which retells the story of a blacksmith whom the Devil considered so evil that he tried to close the gates of Hell to keep him out.

It opens with Basque deserters being lined up for execution. A blacksmith, desperate to return home to his young wife, makes a deal with the devil to escape and return home. He is imbued with seemingly-otherwordly strength and fights his way back home where he becomes a bogeyman of his village. Which, I mean they ain’t wrong.

Regarding the other two aspects of Errementari which make it stand out from other horror films, I would say the Basque mythology connection may be the most unique and refreshing to see on the big screen.

The wonderful tension between Christian and non-Christian beliefs, which lived side by side in Basque country past the 10th and 11th century, is shown through the traditional mystical devil imagery alongside catholic priest figures and a literal hell on display in the final act. Various traditions connected to their ancient belief system have survived partly by adapting a Christian veneer or by turning into folk traditions, as happened elsewhere in Europe. This melding of christian and traditional imagery is seen throughout the film.

And typically seen through the eyes of a little girl. Again, one is reminded of the work of Del Toro. Choosing to situate this film from a youthful gaze adds to the sense of danger and wonder — we are almost put into the role of everyone around her who is punishing, protecting, and worrying for her. And eventually we follow her to the gates of hell as other characters do themselves.

Errementari isn’t for everyone. It isn’t the most slick, high budget, or fast-paced thrill-ride of a horror film. It is, however, a look into a culture not often represented in pop culture. It is also a strange, unique work of art with some wonderful practical effects, moody, beautiful settings, and some real, genuine ambition and heart.

Watch Errementari, and see if you can find sympathy for the devil.