Review: The Evil Dead (1981)

The Evil Dead might be the quintessential cult horror film. I’m sure there are some that came before and some that have come after, maybe you could argue with me that those films better embody the definition of “a cult film.” But I know that for me, this movie was the first I heard referred to as a cult classic. Or maybe it was the first that upon watching it and enjoying it I understood why it was cult-ish — why it wasn’t for everyone. Why the fact that it was for me made it possibly that much better.

It’s like that The Room movie starring shaved caveman Tommy Wiseau. Now I don’t get it — I’m going to be honest, and I’m sure that’s tearing you apart, Lisa. But for those of you who do, and can recite catchphrases like I can with The Evil Dead, it’s probably made that much better because handsome losers like me don’t get why the film is entertaining.

But what does it really mean to be a “Cult Film?” Capital C and capital F. And what does it mean to be a cult horror film specifically?

Well, according to the very UK-ishly named Ian Haigh at (oh that makes sense) BBC News Magazine, one “category of cult film is the “so-bad-it’s-good” (What Makes a Cult Film?). Good and bad are lazy and subjective terms of course, so for the purposes of this post I will be using the term “bad” to refer to being substandard to a high budget Hollywood feature in camera, sound, acting, or dialog quality.

Does The Evil Dead fulfill these requirements. I mean, I love the movie, but yeah. Does it have the polish of a blockbuster Marvel feature? No, of course not. But neither do countless other movies that are just so bad-it’s-full–stop. What sets Sam Raimi’s (who did in fact go on to make blockbuster Marvel features) horror film apart from the other low budget fair that got lost in the bloody shuffle?

According to the director of the cult film archive at Brunel University, Xavier Mendik, films become “cult for an entirely different reason than originally intended.” As in, it’s not about a quality fans in the know see that others don’t understand, but instead, “Fans [often] view the films that they celebrate either with a patronising [sic] affection or even downright contempt” (What Makes a Cult Film?).

All of which isn’t particularly helpful, because that sounds like a bunch of analysis by people who don’t really enjoy cult films that much. Just study it. Because I would say that fans of cult films truly do love these movies and don’t watch them in a contemptuous or patronizing way at all.

Whatever makes something a cult film as opposed to just a cheap one, I think we can all agree that it is impossible to manufacture a cult hit. As was attempted with Sharknado — which, yes, had a moment when it was accidentally so-bad-it’s-good, but then went on to drown itself when the producers tried to repeat their accidental success.

What I do think the BBC article got right was the comment regarding the fans’ connection to the films for some other reason that original intention. Whether we are talking about bad films that end up hilarious, or The Evil Dead, which is a frightfully disturbing and gory film that somehow ends up funny. I don’t think this was entirely by accident, so the theory falls apart a bit, I think Raimi is just a weird guy. I’m not sure he truly knew just how charmingly silly The Evil Dead would be. And I like that.

I think Evil Dead II, while great in its own way, is outshined by the original because of the sequel’s increased self-awareness of its comedy. It might even be a more watchable film, but has lost a bit of the charm of the original. The lightning in a necronomi-bottle that is the almost accidental comedy of The Evil Dead.

But is that all there is to it? A film that is supposed to be serious or scary is just funny? Isn’t that, well, mean-spirited? I mean, maybe that is true for The Room, or Sharknado (actually that picture looks awesome), but you can’t tell me people don’t truly love The Evil Dead and The Rocky Horror Picture Show. They don’t just want to make fun of them. I think it’s less of an accidentally funny sort of thing, though that can be part of it, and more of an accidentally genius sort of thing — my apologies to Ian Haigh. A film, often made by a new or young filmmaker happens to strike a chord with people either through accidental depth, surprising charisma of an actor, or being so unapologetically fresh and original that, despite its failings in some of the more traditional aspects of film criticism, it insists upon itself as worthy of love.

But what does it mean to specifically be a cult classic in the horror genre, and what does The Evil Dead do to achieve this status?

Well, for me a cult horror film separates itself from simply low budge horror films in three ways:

- The film uses the small budget it has intelligently — the picture seeming to be much more expensive than it actually is. But this on its own, of course, does not a cult horror make: see The Blair Witch Project, which was made for 60,000 dollars but is by no means a cult hit.

- The film does something not seen before. I’m not just saying buck the trend and make a vampire movie instead of a haunting. Cult classics in horror have to be a horror film like has never been done before. Like, well The Blair Witch Project, or Halloween. Which is a problem because, of course, neither of those movies is a cult horror film. They are just low budget successes.

- So then, the film must not be for everyone, must achieve success but achieve it almost in secret, and achieve it slowly. It’s that “in the know” concept I mentioned earlier. My father would hate The Evil Dead. Well, he’d probably hate The Blair Witch Project too, but my point is that cult horror classics need to not reach a level of mainstream success of a Halloween. No, they must be legends within the genre. True fans worship at its alter, but the horror cult film is not a crossover.

Why isn’t it as popular? Why doesn’t it crossover? Well, we are talking about specifically cult horror, so I think it has to do with the amount of material that is off-putting. Look at the sometimes very strange effects in The Evil Dead, the over-the-top gore, the sound, the camera. It isn’t for everyone. I mean, good lord, the arboreal rape scene. I guarantee you a lot of viewers have cut the movie off at that exact moment.

So why make a movie like this? Why include such a moment. Is it necessary for the film to have that hard-to-watch scene? This is a good discussion to have about any rape scene in any film, but I’m looking at it only in the context of a cult horror film here. Scenes like that, the off-putting and weird, give such films a unique personality that perhaps detract from their mainstream appeal, but make them more precisely targeted for a specific, smaller audience. One that will love it more for allowing them to be part of the exclusive in-group, which will then exalt the film to cult classic status.

But these films need to not only have these aspects that make them unsuitable for mainstream, but to also have that surprising depth with which that target audience can connect.

So where is the depth in a silly, gory, low budget demon movie? I’d say that a quick dive into how the film features the necronomicon, the mythical tradition of katabasis, and the unlikely similarities it has to James Dickey’s Deliveranceshould clear that right up.

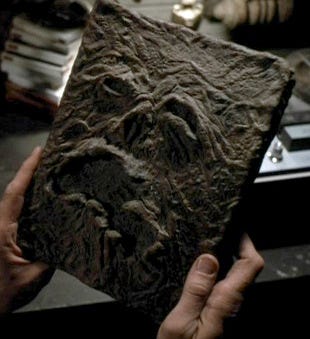

First, as I hope you know if you are reading this post, a major part of the plot of The Evil Deadrevolves around the evil Book of the Dead, or Necronomicon Ex-Mortis. The book is taken from its ancient, I’m assuming sacred resting place in Kandar, taken to a remote cabin, where it is then read aloud and awakens an evil spirit living in the Tennessee woods.

This use of the Book of the Dead is obviously a reference to H.P. Lovecraft’s “The History of the Necronomicon,” which reads a bit like a literary found footage film. In it, Lovecraft describes the book as if he was Professor Raymond Knowby recording his academic observations, observing its original title to be a word to describe“nocturnal sound[s] (made by insects) suppos’d to be the howling of daemons.” The creator of the thing documented as having “spent ten years alone in the … ‘Empty Space’ of the ancients” and “seized by an invisible monster” and a worshiper of Yog-Sothoth and Cthulhu (H.P. Lovecraft). Yog-Sothoth, it is explained in later additions to The Evil Dead franchise, is the ancient entity that rules over the deadites (a person possessed by a Kandarian demon).

What does all of this mean? Well, it means a wealth of references to classic literary horror tradition, strange and intriguing sounding world-building, and a bit of mythos nerds like me can sink our buck teeth into.

It also sets up my next two deep dives: the film’s use of katabasis and its connection to Deliverance.

Now, this elder God mess is fascinating and terrifying. Cthulhu is an unknowable, incomprehensible entity, and so is Yog-Sosoth. They are older than ancient, existing underneath — perhaps always existing there, perhaps they created what is above. They are what is around us, they are nature, they are the planet itself in a way. Maybe the spirit of the Earth is not the motherly, warm Whoopi Goldberg Gaia, but it is evil and fucking hates us.

That is the eldritch horror of Cthulhu, of Yog-Sosoth, the deadite ruler. It views us as an interloper. A cancer. Or maybe not even that, because we spend a lot of time thinking about cancer… is it cliche to say it views us as insects? We’d like to think we have a loving and caring God planning this Earth out for us, but if Cthulhu is our creator then we are barnacles attached to the rusted hull of a long-forgotten shipwreck.

So that is what Ash is up against. The nature of evil, all around him and ancient. And this is where Deliverance comes in. According to John C. Inscoe, Deliverance is at least in part about “the tensions wrought when the sensibilities of modern suburbia are pitted against the more elemental values of the natural world…” and the titular deliverance is in fact the hardships the characters face, which draws their attention to “their own mental and psychological shortcomings as the products of a soft, comfortable, materialistic culture” (Deliverance).

Which brings me to the concept of katabasis, a mytheme describing a “descent of some kind.” In mythic tradition, this descent is seen when “ The hero (Ash) or upper-world deity (suburban outsider) journeys to the underworld or to the land of the dead and returns … with heightened knowledge.” This can be seen in The Evil Dead both in the figurative descent across the bridge into the unfamiliar Southern wilds, as well as down into the basement of the cabin. But what is this knowledge our hero seeks?

In American Poet Robert Bly’s book, Iron John: A Book about Men, uses katabasis to describe the depression felt by some modern men due to the lack of Western initiation rites. Essentially that tension felt by the characters of Deliverance when they become trapped in a place they did not belong to or respect, which ultimately leads to their harrowing, but mostly humbling experience.

I think that The Evil Dead is speaking to this exact same tension. It is no accident that Ash et al are a group of suburban, co-ed, interlopers. And think of some of the first things to show up in the movie: our heroes arrogantly driving all over the road, making fun of “rednecks” waving at them on the side of the road, and generally acting as if they are too good for the rural, natural space they have come to. We see this mirrored in the origin of the evil — Professor Knowby went to Kandar and stole this ancient thing he didn’t understand, then brought it back to this cabin situated in a natural space he isn’t from. It’s just a bunch of colonizing, privileged, educated outsiders shitting all over the place. Butting into where no one asked them to be. Maybe if they weren’t so arrogant, so loud — didn’t take relics for their own purposes, none of the terrifying and bloody events that followed would take place.

One of the more fascinating aspects of this movie, to me, is that the Necronomicon does not necessarily unleash a demon or even contain one. What it does is instead draw out a local spirit inhabiting the woods. I think Yog-Sosoth is not contained within that book, necessarily. The viewpoint katabatic wind chasing the suburbanites between the trees is not from Kandar. The book, written by a worshiper of Cthulhu and the elder Gods, contains spells to draw out local spirits no matter where they are to defend themselves against outsiders.

I think, upon re-watching the film, there are two separate things going on in those woods: The deadites are made by the book, while the surrounding woods are haunted by a Southern spirit that has been awakened. Two separate entities in a way. The nature spirit simply wants to harm, to violate as it has been violated and encroached (Like we see in the assault scenes in both Deliverance and The Evil Dead). The deadites, however, seem to have a different objective than simply violence. “Join us,” is uttered more than a few times by the possessed characters over the course of the film. It is making disciples to spread the book, spread the incantations, spread the magical white blood cells of the Elder Gods to defend the Earth against vacationing yuppies.

And all that awesome referencing within a film made for just 350,000 dollars. With amazing, never-before-seen camera work, a singular performance by a charismatic lead, and a joyful authenticity rarely seen in the capitalistic film industry now-a-days.

So when you hear someone refer to The Evil Dead as a “cult classic,” don’t think “so-bad-it’s-good” or Sharknado, think Cthulhu meets Deliverance if it was made by your best friends in college.