Review: The Exorcist (1973)

Understanding the fact that The Exorcist is fundamentally about the individual of Father Karras, who is the titular exorcist in the film, is central to full appreciating the film as a work of art. This small fact may seem either pedantic or obvious, but it is worth noting due to the film itself running contrary to this in some ways.

We spend time with the family. We identify with the mother, with Regan. Father Karras does not fully get the heroic, successful ending one would expect from a protagonist. However, unlike Tangina from Poltergeist, Van Helsing from Dracula, or even the Warrens from The Conjuring, the wise and helpful outsider(s) to the events is more fore-fronted in The Exorcist. Karras is not simply a font of information, showing up to assist the leads in their journey, but a man on a journey all his own. Both in his faith and as a fully-realized, changing, character in the film.

And when discussing viewpoint in film, this brings to mind perspective. Both literally and figuratively. What was the film trying to say? About what? And how did it say those things?

The writer of the 1971, William Blatty, stated that his intention was to “write a novel that would, not only excite and entertain [more than a simple sermon], but [to] make a positive statement about God, the human condition and the relationship between the two.” Great evil is shown. Great cynicism. Humans in The Exorcist are leaving God, just as the United States’ population was doing as a modernizing country. This is paralleled by Regan’s burgeoning womanhood, a symbolic move from the pure to the tainted mature. Blatty saw this turning from the faith as a threat to the traditional values on which he believes the United States to be founded upon.

This characterization of Regan is directly related to the younger, faithless generation of the 60s and 70s in Blatty’s Eyes. Regan, hip-deep in adolescence, displays a, as Dave Schneider in his fightbacknews.org article “The Exorcist and the right-wing politics of possession notes, “..temperament tak[ing] a dark turn … violent outbursts … unprovoked profanity-laced insults at her mother and others.” These extremized representation of rebellious modern youths prompt her mother, Chris, to seek help for her daughter in modern medicine. Psychology, a turn from the traditional place to seek help for the guidance, the church. Eventually all the science and logic in the world can’t help the family, so they turn back to something many in America, according to Blatty, have left behind: the power of God to heal.

One may wonder why this happened to Regan. Aren’t there thousands of young people in the 60s and 70s who are pushing away from tradition? Who are rebelling? Who are going through puberty and seeming to be almost different people entirely form whom they once were — almost as if they are possessed? I am not sure this question can be completely answered, but the solution may lie with the single mother, Chris. She is independent, self-supporting. Thoroughly modern. She is not occupying a traditional gender role for a woman as understood earlier in the century or lauded in traditional religious circles. Chris’s flirting, socializing, and failure to provide Regan with a solid “man of the house” seem to be a precipitating factor in the possession of Regan. This domestic reality, all too common to the more traditionalist of the christian faith, could be the reason the family is open to invasion by a demon. Barbara Creed states in “Woman as Possessed Monster” in her 1993 text The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis, “The theme of urban and spiritual decay is linked to a decline in proper familial values through the MacNeil family.”

The film, in Blatty’s eyes, is an attempt to wake the public back up. To shake the viewers, force them to see the forces of evil and good that they seem to have turned from. To get them to believe again. Blatty, through director William Freidkin’s film, showed us in full cinematic glory the truth that he believed to have been ignored by displaying through Damien Karras’s sacrifice at the end of the film the “…love as God would love.” His aim was to display the absurdity of man as simply “…no more than molecular structures” by showing the heroic good that could be enacted by someone upon a stranger for no reason other than it is right.

This perspective of the film wasn’t completely necessary to be shown through the eyes of the priest. This same concept could have been presented through the eyes of the mother or Regan herself. They could have witnessed his sacrifice and come to believe in God by the end of the film. But that was not the path taken by Blatty. No, the story is about the exorcist, Father Karras.

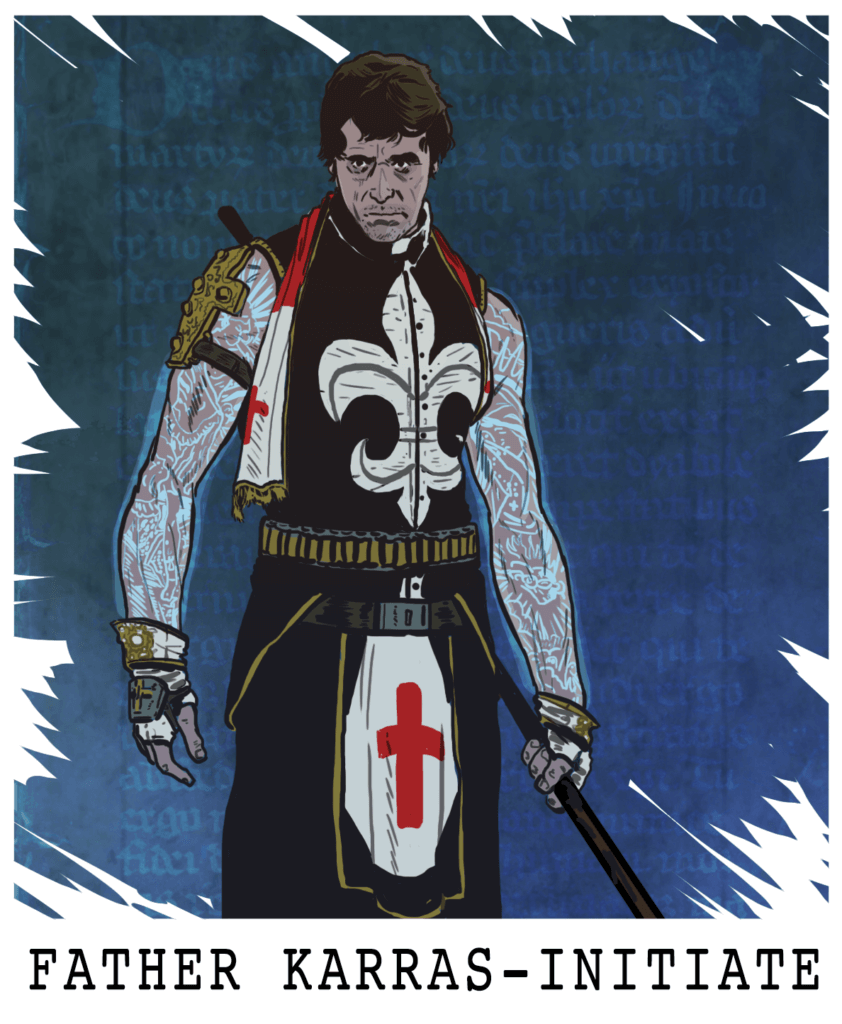

Naming him as the titular character aligns him with other mythical heroes such as Conan the Barbarian or even modern superheroes like Batman or Ironman. The role of Karras in The Exorcist is not a supporting character, even one who saves the day. This is his story. The story of a hero who fights to defeat evil. Though ultimately he falls to that evil, he does so by selflessly sacrificing his own life to help that of the innocent. Evil is not purged from the world, however. It is still out there, still needs to be dealt with, but worry not, there are other priests — valiant heroes of the faith the public doesn’t even realize is watching over them, waiting to take up the call.

Blatty paints a portrait of an under-appreciated, even scoffed at sect working in the shadows due to the unbelieving cynicism of modern Americans, who protect us nonetheless.

In showing us how these selfless priests can, if allowed to do their work, emerge from said shadows to save both the literal souls of the possessed, as well as the metaphorical souls of the faithless, Blatty invites the viewer to:

mak[e] the unconscious connection between the hideous malevolence on the screen and the moral evil in his personal life; because he has recognized that the demon in all his putrescence is the ultimate father to stealing from one’s brother and calling it ‘business.

“There is Goodness in ‘The Exorcist'”, William Blatty

The faith, the forgotten heroic priests are our only salvation from this evil we have brought on our selves. This connection is made to turn the viewer of the film and reader of the novel “back to the sacraments.” Even if most experiencers do this only fleetingly, or simply enjoy the experience, if “…even one soul, for even one moment, to once again be in touch with grace” is the result, then he as achieved his goal in writing The Exorcist.