Review: A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)

It seems like every horror movie, when described by some sort of critic, is valued only for its originality. More than any other genre, horror films tends to be lambasted for being copy cats. The irony is, of course, that the creators of these sorts of movies may be the the most prolific mimics working in Hollywood today.

And maybe “today” is giving the genre too much credit. Hasn’t it always been this way?

This sounds, and I apologize, like I’m shitting on horror movies. So let me be clear: I LOVE HORROR MOVIES. Perhaps more than I love any other genre of film. I do, however, want to look into why critics and audiences seem so hyper-focused on this one aspect of the films. And why when a horror movie comes out that seems to buck the trend, those are most often the ones that remain crouched and waiting behind our subconscious id long after they first hit the big screen.

First, let’s look into why horror creators ape their ideas. My answer to this is, are you ready?: they don’t. Well, let me equivocate. The good ones don’t. Even if two horror films released in the same year seem strangely similar, tapping into the same fears somehow everyone in the nation is simultaneously haunted by, I would argue that these creatives are simply mainlining into a shared subconscious of awfulness. That fear is indicative of the time period in which that film has been situated.

So not copy cats. They are all just commenting on the same shared experience.

So — and I’m not telling anyone anything that hasn’t been commented upon before — one must simply examine the films that terrified audiences the most during any given decade to find out what the paranoia and fears of the populace were at the time.

Giant irradiated monsters during the 50s? That’s an easy one — nuclear panic. Zombies attacking the suburbs during the late sixties and early seventies? Anxieties involving Kent State, Vietnam War imagery, and widespread integration into white spaces. Slasher movies in the 70s and 80s — check out the plethora of serial killer documentaries on Netflix if you are still (gone) in the dark on that one.

My point is only certain things are scary to the United States at certain times. Fantastic films that gripped the entire nation in a cold fear now are literally laughable at times—like Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, despite its undeniable important impact on the horror genre.

So why, then, do some horror movies stand the test of time? Why do we always come back to John Carpenter’s The Thing or William Friedkin’s The Exorcist, or, you guessed it, Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street?

The obvious answer is, of course, that the fears they tap into are timeless and universal. That is a vague statement — one which we have all heard in some form or other if we have read any amount of horror film criticism. So what does that mean? What makes a fear universal as opposed to temporal — like the 50 foot woman from 1958, the decade of the rise of the term “nuclear family” and a particularly single-minded Hollywood propaganda machine reinforcing traditional gender roles as a new way for women to “fight the commies” (Khan Academy).

Doing an irresponsibly brief Google search, I found that three of the most common fears according to Karl Albrecht Ph.D are extinction, mutilation, and loss of autonomy (The (Only) 5 Fears We All Share). The last two are fear of abandonment and shame. Which, do apply to A Nightmare on Elm Street in the form of Nancy’s father (abandonment) and mother (shame),but I don’t have much to say about those, so fuck it.

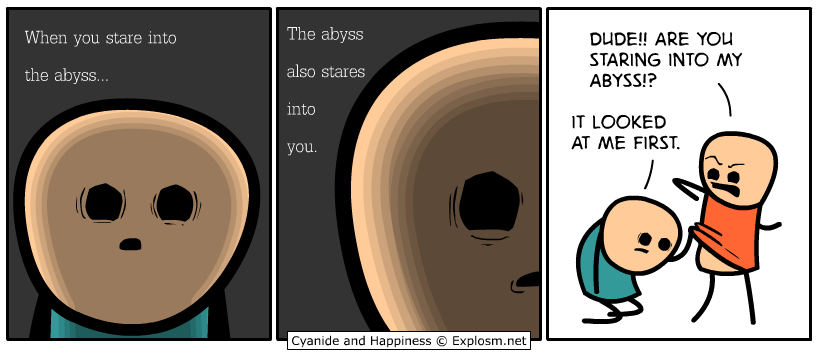

Let’s look at extinction. It’s the fear of death, of annihilation, of ceasing to exist. It the instinctual panic you feel looking into the unknown. That existential terror Nietzsche described as happening when “gaz[ing] long into an abyss, the abysswill also gaze into thee” (Beyond Good and Evil).

I take this as a sort of annihilation of self. Of a fundamental change in someone at the core level to where there is almost nothing left of them. People become what they love and hate because of their obsession with these things.

So does this play into why we are still afraid of Freddie Krueger? Is it because he is so evil? I dare say Nietzsche thinks it goes beyond that. Get it?

No, we are terrified of Freddie, even if we don’t know why, and always will be, because we can see ourselves in every aspect of him. See our own annihilation staring back at us out of his abyss (his life story).

He is a monster, a terrible person, before he is turned into a nightmare version of his former self. However, we can see through his transformation that he originally was just a man. And those parents who obliterated him in such a violent fashion, we can perhaps see ourselves even more clearly in their righteous, almost gleeful vengeance. Krueger will always scare moviegoers because his story is one of losing yourself by staring into that abyss just a bit too long. And becoming the monster you hunted.

And it is no coincidence the film happened to catch fire (pun intended) in the middle of Reagan Era politics in the US. In a time where a hyper conservative America was almost violently responding to years of progress through women’s liberation and civil rights movements. White America pushed back with their ballots, and it seemed women and minorities were again under attack. There might have been some sort of gnawing fear that the sins of the past might be coming back to haunt their nightmares.

Mutilation, of course, is another reason why Freddie has never left the horror zeitgeist. Mutilation, is described by Dr. Albrecht in Psychology Today as “the fear of losing any part of our precious bodily structure; the thought of having our body’s boundaries invaded.” This speaks to A Nightmare on Elm Street in a few way:

- Freddie himself has a mutilated face, creating an uncanny valley in his features and a fundamental unease in the viewer while watching him. Even in the way he manipulates his body, through surrealistic elongation, and self mutilation, we see this universal fear of losing body integrity and pushed boundaries being encroached.

- “The Terrible Place” according to Carol Clover is one of the fundamental elements of a horror film, especially Slasher films like (half of) A Nightmare on Elm Street. This Terrible Place is the location, containing a violent past, where the killing occurs. Crystal Lake on a specific Friday, the suburbs on a certain spooky holiday. But the Terrible Place in A Nightmare on Elm Street is, in fact, within the characters’ own minds. Their dreams — which is universal in its terror due to the fact that all viewers may not vacation at the lake or live in the suburbs, but we all dream (“Her body, himself”). We can all have our mind’s boundary invaded.

- And finally, Dr. Albrechts expands the definition of mutilation to also include “Anxiety about animals, such as bugs, spiders, snakes, and other creepy things [which] arises from fear of mutilation.” Freddie Krueger wears the claws of our most primal predator, dating back to the stone ages — a time with no lights and no telephone to call for help. He uses the weapons of the cave bear. Without exhausting the subject any more, Freddie Krueger is also the horror surrealist figure, often, much like the 1929 film by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali Un Chien Andalou, changing his body into disturbing distortions of the human figure. Breaking the boundaries of what the human body should do. He is creepy, like Un Chien Andalou is creepy, because it forces us as viewers to imagine our own bodies subjected to such horror. It challenges us, pushes us past our boundaries.

The third and final timeless, universal fear, as Dr. Albrechts points out, is Loss of Autonomy. He describes this as “the fear of being immobilized, paralyzed, restricted, enveloped, overwhelmed, entrapped, imprisoned, smothered, or otherwise controlled by circumstances beyond our control”(The (Only) 5 Fears We All Share). This is one of the main horrifying elements of A Nightmare on Elm Street.

It isn’t the striped soft top car, the goofy elongated arms, or even the gore that sticks with audiences over the years. It is that violation of our given understanding that at the end of the day we can recharge our batteries. We can lay our heads down to sleep, start over again. No matter how horrible the previous day was.

Freddie Krueger takes that away from Glen and Nancy. They are not allowed to go to sleep. They are trapped by their own bodies and ultimately betrayed. And there is nothing they can do about it.

So yeah, horror critics and horror fans seem to be obsessed with originality of films. Its an arms race of fear, always backed by a capitalistic enterprise, so I don’t fault anyone for chasing a trend. But it’s the truly clairvoyant films, those films that aren’t only tapping into the paranoias of the era, but instead speak to universal and everlasting fears of everyone, that truly stand out as classics in the genre.

It makes sense, then, to focus so much on which movies stand out apart from the decade in which they were filmed. The films that don’t seem to simply repeat ideas from other popular movies the year before. The fears touched on by A Nightmare on Elm Street are timeless and ubiquitous, and just as terrifying now as they were in 1984. Perhaps even more so now than ever.